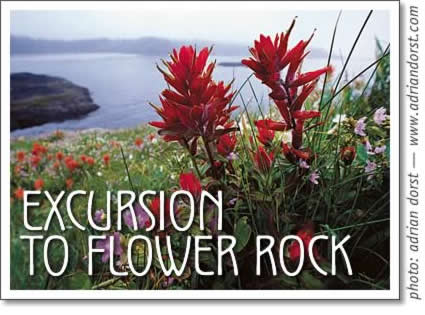

Excursion to Flower Rock

by Adrian Dorst, Tofino

My kayak slices through a kelp bed and glides into a tiny cove protected from the ocean swells. Or so I hope. I reach out to grasp the slippery, seaweed-covered rocks on the port side, but the sea slowly rises and falls. With a combination of agility, timing, and luck, I succeed in extricating myself from the boat and planting my feet on terra firma. Then, grabbing the bow of my boat, I haul it ashore, well out of reach of the rising tide.Boat secured, I look around. I am on the lower part of a dome-shaped rock that lies offshore from Vargas Island, just five miles from Tofino. Cement and pavement may dominate in the village, but here on this rocky outpost, nature reigns supreme. Harlequin ducks in breeding finery splash among the reefs nearby, while black oystercatchers create a din as they chase one another in mating ritual. Overhead, a resident osprey scans the sea for coho. The eagle that had been watching my arrival from atop the wind-swept spruce is gone now, but I don't mind, today my focus is on wild flowers.

Vivid splashes of Technicolor greet my eyes as I look up—deep reds, oranges and vivid yellows, against a background of green, dotted with purple. I grab my camera bag and tripod and proceed upward, taking care not to step on the vegetation, at least when that's avoidable. The weather is nearly ideal for flower photography – overcast with a light drizzle – but a light breeze caressing the flowers makes conditions somewhat less than perfect. Depth of field can be a problem when the subject is in motion. Nonetheless, its as close to perfection as one is apt to get on the outer west coast and I'm a happy man.

Close-up, the bright splashes of color have metamorphosed into plants called Indian paintbrush, yellow monkey-flowers and Siberian miner's lettuce. On the side of the cliff, a cascade of monkey-flowers attracts my attention. I set up tripod and camera, take a light-reading with my hand-held meter, adjust aperture and shutter speed and peer through the view-finder. The shutter clicks once, twice, three times. I get up and wander like a hummingbird from bloom to bloom, praying that the wind will lay low.

Here and there among the verdant growth I see signs of other visitors. A barely perceptible trail runs through the vegetation, created by mink, which apparently use this isle as a base for raiding the inter-tidal pantry that surrounds it. And emerging from a cleft in the rock on a low cliff face, I see a path so well trodden, it can only mean that the mink's larger cousin, the river otter, is also a resident. Familiar with the otter's preferred lounging requirements, I decide to climb up toward the summit for a look.

I circle the cliff and fight my way through dense scrub into an open area beside the island's only tree, a Sitka spruce that, although small for its species, looks ancient. The trunk is a metre wide at the base, and for a short distance runs parallel to the ground before rising to a maximum height of about 6 meters. The contorted, wind-swept branches are festooned with hanging beard lichens of the Usnea genus as well as large clumps of leathery polypody, or Polypodium scouleri, a relative of the licorice fern endemic to the salt zone of the outer coast.

So dense is the foliage overhead, it forms a protective canopy that shuts out the sky. Where I am standing, the ground is bare, forming a perfect playground for fun-loving otters. A well-traveled otter freeway is visible descending from the scrub-covered summit.

Somewhere nearby will be a pool of rain water which serves the otters as a bath to wash sea salt from their fur. I know this from having visited other rocky islets similar to this one over the years. Inevitably, at or near the summit, usually in a place that affords a splendid view of the surroundings, and often beneath a canopy of branches, I would find the earth similarly bare, with a pool nearby for bathing. While this arrangement serves otters in a practical way by providing them with a safe place for lounging, as well as bathing, it appears that these intelligent animals also prefer a penthouse suite with a view.

Later, in the meadow below the terraces, I find the breastbone and skull of a bird – a surf scoter, I conclude, devoured by an eagle. From my favourite campsite on Vargas, I often see bald eagles perched here in the flower meadow, or on top of the wind-swept spruce. All three species, I realize, mink, otter and eagle, contribute to the ecology of this rock garden by depositing organic material through what they haul ashore, as well as through the excrement they leave behind.

Flower Rock has not always looked like this. During the last ice-age, when sea levels were hundreds of feet lower, this would not have been an isle at all, but merely a rocky hilltop, miles from the sea. In fact, judging by striations caused by glacial scouring on rocks on nearby Vargas, at one time this area was buried beneath a mantle of ice. What I have no way of knowing is whether the scouring happened during the peak of the Fraser Glaciation some 15,000 years ago, or a previous one. Scientists believe as many as 13 may have come and gone in the past million years.

Soon after the glaciers melted about 10,000 years ago, sea levels in this area were some 50 meters higher than they are today. This rock would then have been far beneath the ocean's surface. As the water gradually receded and areas of the rock became exposed to stand above the reach of storm waves, plants such as villous cinquifoil, seaside plantain and hardy grasses colonized, as indeed they are still doing today nearby. Clutching minute amounts of soil with their roots, these pioneers prepared the way for other plants. Fertilized by otter, mink and eagle, soil fertility gradually increased to the point where the verdant flower gardens I am seeing today are able to flourish.

People may also have played a part in the ecology of these gardens. Similar domed rocks on this coast are often topped by shell middens, indicating that they were used seasonally by the native Nuu-chah-nulth as a base for gathering seafood such as mussels, urchins and abalone. On this rock I see no sign of a midden, nor do I see a place suitable for that purpose. However, on nearby Vargas Island, a shell midden exposed by a toppled tree suggests that they chose to camp in that more sheltered location. It would have been a small matter for them to canoe from there and land, as I did, in the sheltered cove below. Besides gathering food from the inter-tidal zone, the Nuu-chah-nulth may have arrived to harvest plants as well. Nodding onions, who's roots and flowers impart a delectable flavour to soups and stews, and which, when eaten raw stimulate the appetite, grow in abundance in the meadow. And on the steep north-east side of the rock, in places sheltered from the wind, cow parsnip is much in evidence. The young stems are said to have been peeled and eaten in the manner of stalks of celery.

Looking down at the abundant growth of Siberian miner's lettuce at my feet, I wonder if this plant was also harvested for food. After all, its cousin Claytonia perfoliata, distinguished by round leaves, is quite palatable, if not actually flavourful. I chew a few leaves of Claytonia sibirica but gag and spit it out as the oxalic acid burns my throat. I have been quickly and effectively dissuaded from my hypothesis. I read later in Plants of Coastal British Columbia that Nuu-chah-nulth women used it in times past to induce labour.

Near the crest of the meadow, I set up my tripod and camera where a particularly attractive cluster of paintbrush have taken root. Despite the fact that some of the blooms in front of me are orange in colour, I suspect they are all common red paintbrush, or Castilleja miniata, as they are known to botanists. Although there may be 40 different species from seashore to alpine, or only half that many, I don't trouble myself to differentiate, as even the experts can't seem to agree. I prefer the name Indian paintbrush, which is the name used locally. Surprisingly, the magnificent blooms I am looking at are technically not flowers at all, but brightly pigmented leaves or bracts serving the function of petals.

As wind and rain pick up and it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain depth of field, I decide to call it a day. Besides, after several hours exploring the rock and exposing three rolls of film, I have just about exhausted the photographic possibilities. I return to my boat, stash the camera bag in the rear hatch and seal it carefully with the flexible hatch cover. Then, I haul the boat back to the water and with great care, launch it at the crest of a rising swell. I scramble to get in without upsetting the kayak.

Success! I am securely seated and feeling rather smug about my dexterity and skill, when the impossible happens. To my utter disbelief, and as if in slow motion, I watch helplessly as the bow disappears beneath the water and the kayak is abruptly wrenched upside down with me in the cockpit.

The cold water shocks me into action. I struggle to the surface and my first thought is for my cameras. I flip the boat right side up and, still clinging to it with one arm, reach out with the other and attempt to grip the slippery, seaweed covered shore. The receding swell, it seems, has other ideas and drags me down, breaking my hold. After several attempts I succeed in clutching a protruding rock at the top of an incoming swell and struggle ashore. I pull the boat up behind me and with bated breath open the hatch. Almost miraculously and much to my relief, the camera bag remains dry. Cold and wet, I clamber into the boat once more and paddle towards Vargas Island.

Little more than half an hour later I am sitting stripped down, but none the worse for wear, beside a crackling fire on Vargas with Flower Rock visible in the distance. With a cup of piping hot tea warming my hands I have a chance to reflect on my mishap. The answer, it turns out, is quite simple. The bowline dangling over the side had become ensnared in the bull kelp anchored to the bottom. When a rising swell lifted the boat, the line prevented the kayak from rising with it. The tension on the line that was attached to the bow flipped the boat. Another lesson learned. I concluded long ago that if you succeed in surviving enough mishaps, you may actually live long enough to become an expert.

Raising my binoculars, I look back at Flower Rock. From here, the flowering blooms are once again mere splashes of red and orange and yellow, as though painted by an artist's brush. But near the summit, atop the spruce, sits a large dark bird with a white head. The eagle is back. Once again the rock belongs to its wild denizens alone, the eagle, otter and mink. At least until next year, when I'm bound to return to wander among the magnificent blooms once again. And there's one thing you can count on. This time I'll be sure to secure my bowline.

Adrian Dorst is a Tofino nature photographer, carver, and birdwatching guide. His photos can be found in our photo gallery or on Adrian's website at www.adriandorst.com.

Tofino Kayaking Articles

- A Foggy Adventure May 2002

- Don't be a Speedbump July 2002

- Excursion to Flower Rock April 2003

- Kayak: Keeping it Simple June 2002

- Kayak: Keeping it Together May 2006

- Kayak: Leadership July 2004

- Kayak: Leaving a Margin for Error September 2002

- Kayak: How Not To Do It January 2003

- Kayak: Playing in the Waves December 2003

- Kayak: Time Well Wasted August 2004

- Living Off the Land January 2003

- Tofino kayaking introduction: Paddling Basics June 2011

- Tofino kayaking: Paddle with Friends April 2003

- Paddling through the seasons October 2002

- The West was Never Won August 2002

- Staying out of Deep Trouble January 2008

- Tofino Kayak Tips: To roll or not to roll? August 2009

tofino | tofino time | activities | accommodation | events | directory

maps | travel | food | art & artists | photos | horoscope | tides

search | magazine | issues | articles | advertising | contact us

hosted in tofino by tofino.net & studio tofino

© 2002-2014 copyright Tofino Time Magazine in Tofino Canada