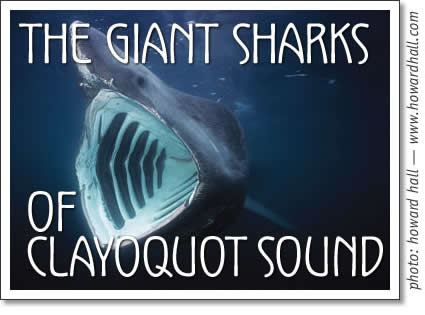

Basking Sharks: The giant sharks of Clayoquot Sound

by Jennifer Nichols

I have never thought I needed to worry about sharks when surfing in Tofino because I thought the local ocean is shark free. I am right and wrong. There are sharks in BC's Pacific waters. The second largest fish the world - the Basking Shark - is said to live here in the summer and fall. And I should worry. This gentle ancient creature - an extraordinary member of our marine ecosystem - could disappear forever.At one time basking sharks were plentiful and easy to spot. Basking sharks are born two metres long and can grow to be over 12 metres long. They slowly cruise the temperate oceans with their enormous mouth wide open sieving out plankton. They "bask" placidly at the surface of the ocean swallowing billions of small crustaceans and fish larvae as seawater pours from the gills that encircle their neck. They were once regular visitors to Clayoquot Sound.

They have an estimated lineage that spans over 30 million years. Their size and long history makes them a probable real-life explanation for ancient tales about sea serpents. However, their historical resilience has quickly been undermined by short-sighted bungling in the last century. This unique fish that existed for so long has quickly been wiped out.

The shark was hunted during the 1940s for oil in its massive one-tonne livers. In the 1950s to 1970s the federal government launched an aggressive eradication program in Barkley Sound after receiving reports of the sharks getting tangled in salmon gillnets.

The history of how the basking shark was targeted is chronicled in the book The Basking Shark - the Slaughter of B.C.'s Gentle Giants by marine biologist Scott Wallace and maritime historian Brian Gisborne. The book describes how the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) deemed the fish a "Destructive Pest." As part of the eradication program the Department mounted a heavy metal knife on the edge of an active fishing vessel. The knife was positioned to skim the surface of the water in order to slice the sharks in half as they languished over their fish buffets.

The eradication program worked. Population declined 90% within the 60 years since the program was launched. Since 1996 there have been only had six sightings.

Scott Wallace continues to research and raise awareness about Basking Shark recovery. He is part of a small number of people studying the shark around the globe. Some of his colleagues have been able to tag about ten basking sharks with satellite transmitters. They found one shark traveled from the UK to Newfoundland. "What that means is that maybe there are basking sharks in Canadian waters that go to Japan," explains Wallace, "these animals may be less localized than we assumed them to be, maybe they are not in bc waters because they don't need to be."

Yet, Wallace is skeptical of the possibility of their abundance elsewhere. "They prefer plankton-rich areas and that is also where most productive fisheries are carried out" he says, "and even though they aren't mammals they do spend time at the surface, ... there are a lot of vessels using these waters--you would expect people to see and report them if they were around." After years of researching the sad history of Canada's most endangered marine fish, Wallace has never seen one, "it's like writing about sasquatches or unicorns" he admits.

These days Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans approach the fish in radically different way. The shark--now recognized by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as an endangered species--is now being considered for legal protection under the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

The DFO recently completed a public consultation to help inform their decision whether to legally protect the basking shark under the SARA. They are pulling together the results of the consultation to determine both the recovery potential and the socio-economic impact.

I spoke with Karen Calla SARA manager for the Pacific Region about the SARA listing process. "With their current abundance there doesn't seem to be a significant socio-economic impact in this point in time." Regarding the benefits of SARA status she said that, "listing of the species under SARA does bring about some automatic prohibitions against killing, harming and harassing."

Even with legal protection under the SARA, it is difficult to know whether this species will ever be able to mount a full recovery. If basking sharks reappear in Clayoquot Sound this summer, it could not hurt to have them legally protected. As it stands now, it would be difficult to prosecute anyone for harming a basking shark.

The ocean is home to a myriad of microscopic organisms. Reflecting on this Scott Wallace points out a bigger issue; "the fact that something so big could disappear without anyone knowing or caring - just think about all the small things that could disappear."

Jennifer is a founding member of The Water Team, a clean water foundation, and has a master's degree in sustainable development.

tofino | tofino time | activities | accommodation | events | directory

maps | travel | food | art & artists | photos | horoscope | tides

search | magazine | issues | articles | advertising | contact us

hosted in tofino by tofino.net & studio tofino

© 2002-2014 copyright Tofino Time Magazine in Tofino Canada

Basking sharks, the second largest fish in the world, are said to live in Clayoquot Sound in the summer and fall. The once plentyful Basking Shark has seen population decline of 90% in the last 60 years and is now considered for protection under the Species at Risk Act.