Oyster Farming in Clayoquot Sound

by Pat Koreski, Tofino

Be careful when you read the "Buy & Sell", you may end up an oyster farmer, or at least that is what I did. I saw a small oyster farm on Lasqueti Island advertised for sale in 1995. I was working at the Coast Guard Station at the time and went and looked at the 'for sale' farm. Upon returning I started talking to local oyster farmers and ended up buying into one here in Clayoquot Sound. I don't regret it. It has been a real learning experience and is helping to keep me in shape, boy is it.Oyster farming in the Pacific Northwest of Pacific oysters, has been going on for over one hundred years. The history of oyster farming in Clayoquot Sound alone is a long and interesting one I will leave for someone else or another time.

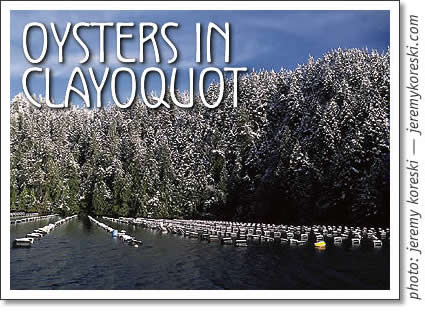

I grow oysters in deep water, strung on small two stranded rope or twine, which hangs down off main lines suspended from 45 gallon barrels. The oysters are set on shell and submerged all the time, unlike intertidal beach oysters. This makes them marketable sooner than beach oysters because they are capable of feeding all the time. The barrels are 8-12 feet apart, lay on their sides and have a main line attached to each end. The main lines are either attached to the shore or to large cement anchors on the bottom. The strings usually hold about 12 clumps of oysters and are tied to the main line about 14-18 inches apart.

This is the preferred method of grow out among the growers in Clayoquot Sound but other methods are available. Of course beach culture, mentioned earlier, was originated by Mother Nature. A variation of the stringing method is to use one inch plastic tubes that are six feet long and have oysters growing on them. These are called "French Tubes" for some reason. Another method, becoming it seems, the most popular method, is tray culture. Trays come in a variety of shapes and sizes and are being improved upon all the time. Tray oysters are for the shell market (oysters sold whole). Oysters grown on strings are mostly for the shucked market (meat only). Some of us are presently looking at using trays as well as strings.

You may wonder how the oysters get onto the shell. Clean, bagged oyster shells are hung in the wild, or more often set in tanks, where free swimming oyster larvae (baby oysters) attach themselves to the shell. I like to have 10-20 baby oysters on each shell. These shells with the babies are then put on the two-stranded rope (euphemistically called oyster blue). The shell is inserted between the two strands about 12 inches apart with an average of 12 shells per string. They hang down in the water about 18 feet.

I have experimented with buying larvae direct from the hatchery and setting it on the bagged shells, called cultch, myself. One method I used consisted of making a pile of about 100 bags of cultch (100-150 shells each) stacked on the beach and wrapped in a tarp. The tarp effectively makes an enclosure and the larvae is sprinkled on the shell as the tidal water flows among the bags of netted shell. I used 4 million larvae for 100 bags. This is called cold setting. I also did a cold set in my workboat. It is an ex-herring skiff; a 28 foot open aluminum boat. This gave me more time as I could control the flow of water instead of being dependent upon the tide. I have had limited success with this method. Not counting my labour it is as expensive as buying the seed already set. After hanging in the water 24-40 months the oysters are harvested into my skiff. All the harvest boats are rigged to lift the main line and also to lift the strings, once cut loose from the main line, into the boat. Some processors want the oysters cut into individual clumps and some will take the oyster string intact. Various growers harvest between 60 and 180 gallons of oysters per skiff load depending upon their boat size and what the processors can take at a time. This also depends on the weather. This winter some of us brought in loads of oysters in, you might say, less than friendly sea conditions. This December was very busy and I alone sent out 13 skiff loads of oysters. This amounted to 1577 gallons of product. More oysters than I could slurp in a lifetime.

The environment the oysters are grown in is very special and important to all of us. It is too bad more data wasn't collected pertaining to each site before the farms went into operation. I know from experience the artificial reefs created by the strings and infrastructure of the farms (I have 18,000 strings in the water sometimes) becomes home to a myriad of marine life. This life in turn feeds fish, birds and other forms of life. This is artificial and needs to be monitored and studied. That is why I am strongly supporting a project that is doing just that led by the Centre for Shellfish (csr) at Malaspina College.

The deep-water industry has been growing slowly over the past 20 years and is now really beginning to gain momentum. I would estimate there would be between 40 & 50 thousand gallons of shucked oysters coming out of Lemmens Inlet this coming year. However, there is a lag in processing facilities and marketing so the oysters are sometimes waiting much longer than necessary to be harvested. Some of us are looking at diversifying our product and perhaps growing mussels, scallops or other lines of seafood in order to not put all our eggs, so to speak, in one basket.

Some of us are also looking at marketing some of our oysters under our own label. They would be custom shucked in a certified plant and brought back to be sold locally or shipped wherever the oyster gods take them. Look for locally grown shucked oysters this coming year in local restaurants and retailers.

Pat Koreski happily farms oysters in Lemmens Inlet. He proceeds with caution now when reading the Buy & Sell.

Tofino Time Magazine February 2003

- New Community Hall in Tofino

- Oysters in Clayoquot Sound

- Comic: The Cheese Club

- Events in Tofino

- Surfgear for Beginners

- Tofino golf: Get a Better Grip

- Tofino hiking: On Lone Cone

- Art & Science of Facials

- Red Door - No More

- Steaming Hot Tofino Winters

- Treating the Winter Blues

- Tofino artist Keith Plumley

- Tofino art: Penny Birnam

- Community Directory

tofino | tofino time | activities | accommodation | events | directory

maps | travel | food | art & artists | photos | horoscope | tides

search | magazine | issues | articles | advertising | contact us

hosted in tofino by tofino.net & studio tofino

© 2002-2014 copyright Tofino Time Magazine in Tofino Canada